In Marrakech buildings don’t have a façade. They come without one. The buildings in the old city, the medina, I mean. Sure, the bending paths through the city that are lined with walls. But these walls can’t really be called facades. One often can’t tell where one building ends and another one starts. There are walls and even more walls that are all finished in pretty much the same way. And all these walls are in same state of disarray. The only thing that punctuates and thereby defines the walls are doors. Doors that lead to an architecture you couldn’t have imagined from the street. This is the miracle of Marrakesh.I have never been to a city that is harder to navigate that Marrakech. Our guide, the Lonely Planet, advises visitors to use a compass. There are all these streets, they all go in a different direction and none continues another. It’s a labyrinth. Since the locals mostly like to get paid to show you the way, navigating this city is either costly or very annoying. Or charming, when you are willing to take your time - which is advisable.The city is so hard to navigate because it has not only hardly any recognizable facades, but also no landmarks in the sense that we know them in the West. The walls that line the streets meander and vary in height, but don’t achieve to form something coherent like a façade. The narrow streets make it impossible to look over the walls and recognize a larger building mass in the distance. The position of a big building can only be derived from the fact that the streets suddenly change their course to circle around it. These walls are like the back of the buildings. The people don’t seem to care about. Maybe the desert climate forced them to do so.Halfway the four-and-a-half day visit to Marrakech my girlfriend and I were shown how to navigate this city by two French couples. In Marrakech details are landmarks: a peculiar electricity tower, the name of a café, a particular sign, a certain shop. Moving through this city is precision work, precision that our tourist map of the city lacked completely. Really nobody seems to care about how these paths run. I wonder if the people in Marrakech expect them to change their course once in a while.What marks the location of a house, mosque, restaurant, palace, school and so on is… a door. A highly decorated wooden or steel door. No big portico or grand staircases, really just a door. Even the grandest palaces start with a simple door. And they aren’t necessarily located at the major streets. The most significant palaces in Marrakech are found at narrow and dark back alleys. To find these buildings you get instructions like: take the first left, then right, then left, again left, right, another right and then finally left.The most elaborate entrances we found was a door with some Arabic tilework around it (see first photograph). It is a door+, still no façade. It made me think of this: has the idea of the façade throughout history evolved from the door? Does a façade start with a door? Does the essence of a façade lie with the door? I think so.The fascinating thing about Marrakech is that simple doors can open up to superb architectures focused at spacious and decorated courtyards. The representation one lacks at the outside, is put on the inside. The level of contrast between the outside and the inside is hardly seen in the architectural practice in the west. Searching for ‘truth’ in the representation of the façade a rich interior is often ideologically reflected in a rich exterior. The Seattle Public Library for instance is as spectacular on the outside as on the inside.In Marrakech we stayed in two its former palaces (riads) that were turned into luxury guesthouses. Although each palace has its own style, they are all feature the same typology. A riad is organized around a greatly finished, perfectly square courtyard. The rooms usually occupy one side of the courtyard at the first floor or, if the riad is a little higher, on the second floor too. Shared spaces (like a lounge, living room, and dining room) and the service areas are located on the ground floor. On the roof there is a terrace overlooking the city.Staying in these riads was amazing. In contrast to the chaos of the city, the courtyard palaces provided a stunningly calm. Silence, fresh air, a bath… this introverted architecture makes the city work.After being in Marrakech for a couple of days I wondered whether or not the Romans lived like this. The old city of Marrakech was largely build in the sixteenth century, not around the year zero and the streets are definitely not organized in a grid, but if you look past the Arab decoration, the courtyard typology definitely has something of the Roman Domus. But maybe I see too much in it.What also struck me was that old city of Marrakech with its impoverished walls, labyrinthine layout and improvised streets on first sight looks like a slum. I therefore wonder what we could learn from this city to improve the ever growing slums in cities all over the world. Does the courtyard typology provide the solution? A Marrakech solution?

|

| Marrakech (Photographer: Marieken Oostrom) |

|

|

| Marrakech (Photographer: vtveen/Flickr) |

|

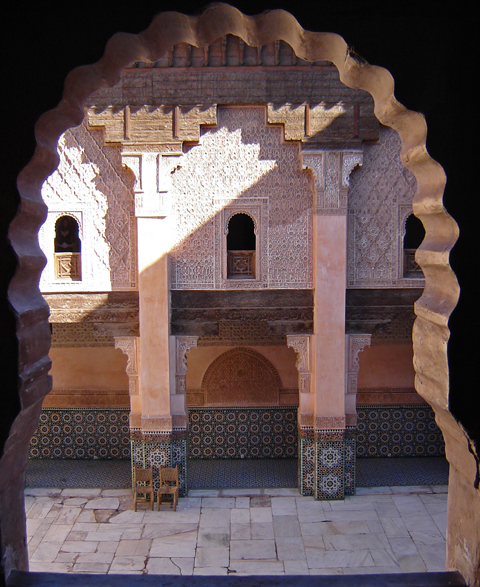

| Marrakech (Photographer: Einalem/Flickr) |

|

| Marrakech (Photographer: vtveen/Flickr) |

Marrakech 2: Souks

“No, that would give the wrong idea”, our twenty something chauffeur answered when we asked him whether he went to clubs. He was married and had a kid, he told us. In Marrakech you go to a club to meet a future wife. You don’t just go partying with your friends. When asked what his wife does, he answered that she cooks and takes care of their kid.

Public life in Marrakech is dominated by men. Sure, there are women in the streets, but they form a minority. Our chauffeur on Friday took us to a Berber market outside of the city. The local Berber community does their shopping once a week at such a market. Pretty much everything one wishes for in terms of food and non-food is sold there. But on about three hundred men, we found a only couple of women duck away in the back of the stalls. This definitely is a men’s world.

When asked where all the women were, every time we got the same answer: at home cooking and taking care of the kids. We soon found out that there was a certain logic behind this. Compared to the west, Moroccans get a lot of children - more than half a dozen per family. In addition to this, it turned out that the locals don’t go to restaurants and cafés. Everybody eats at home. The restaurants and cafés in Marrakech are just for the tourists and the French expatriates living there. The prices are accordingly: about two-third of what one would pay in Amsterdam.

Back in the old city, rows and rows of shops - the souks - provide a kind of permanent Berber market. The shops are run by men, obviously, and all prices are negotiable. Every shop owner asks you for your nationality. For a reason, we read in our Lonely Planet guide. There is a virtual list of nationalities organized to what they are willing to pay. The list is topped by the Americans, the Dutch are put on place eight. We are cheap, apparently. The funny thing is that it seemed to work in our advantage. After theatrical negotiations, some of the shop owners were willing to give us a good discount.

In the long and narrow souks, the shops display everything they have. The shops don’t seem to have a storage area. This in contrast to what we are used to in the west, where in for instance a shoe store only exemplary ‘samples’ of the sold products are on display. The precise product is stored in the ‘back’.

In the city of Marrakech the souks form a complex, continuous network of alley’s. A typical souk consists of a double row of small shops and has some kind of roofing to shed the street from the sun. Officially these are public streets, but since the souks are roofed and the shop owners collaboratively intervene at any disturbance - as we saw happening a couple of times - these spaces at least feel semi-public. Is the shopping mall a public or private place? In the souks, we didn’t know either.

When we took a tour into the nearby Atlas mountains, it turned out that the road - that is driven by a lot of tourists - was lined with shop displays all the way into the mountains. Everything we saw, was only there because of the tourists, our chauffeur explained to us. Along the road an alternative economy didn’t exist. The profit from agriculture (oranges, olives, etcetera) can’t compete with the earnings from tourism.

When we got out of the minicab in the village the road terminated, we took a stroll up to a waterfall. Again, the path was lined with shops. All just for the tourists, our guide explained.

Everywhere tourists come, shops pop up. A continuous shopping mall from Marrakech is being built all the way up to this waterfall. In a couple of years this little walk into the mountain might well have turned into a souk. In Morocco you can’t escape from the souks.

Marrakech 3: Walls

| Marrakech (Photographer: vtveen/Flickr) |

| Marrakech (Photographer: Marieken Oostrom) |

| Marrakech (Photographer: vtveen/Flickr) |

|

| Marrakech (Photographer: Marieken Oostrom) |

|

| Marrakech - Wall around the medina (Photographer: Patrick Mayon/Flickr) |

I suppose most cities around the world strive for a certain coherence in their urban fabric. Even if the urban fabric is a patchwork of different neighborhoods, built at different moments, a certain continuity in terms of density and height is aimed for. Not so in Marrakech.

The old city of Marrakech is walled and surrounded by a band of parks, detached houses and wastelands. Beyond that band there is the Ville Nouveau (a second city center built in the nineteenth century) and other neighborhoods. The different neighborhoods are again separated by wastelands. In the end, the city of Marrakech is composed of isolated chunks of city. Some of these pieces are densely built, others less densely. What is the logic of this city?

In the Netherlands urban planners without exception strive for a city that has a dense urban core with some less dense urban neighborhoods around it and suburban neighborhoods beyond that. Moving from the city center to the periphery the density of the urban fabric gradually decreases. In Marrakech however the central and peripheral neighborhoods have a comparable density. One of the effects of this is that as visitor you have no clue whether or not you are in the periphery or not. When driving out of the city, the urban fabric at a certain moment just stops.In the ‘chunky’

urbanism of Marrakech the neighborhoods have a clear cut perimeter that, because the neighborhoods border an open space, work as a kind of façade. Each neighborhood has a front. The most extreme example of this is the old city itself, the medina. Whereas the buildings inside the medina don’t really have a façade, the wall compensates for this to act like one.

What I find fascinating is that the idea of the walled city has been appropriated by the developers that are building massive resorts along the Route de l’Ourika to the Atlas mountains. The resorts that are popping up there are all walled in a way that reminds to the wall around the medina. The walls around the resorts are therefore cleverly contextual. Along the road the resorts present themselves with their wall. Again the wall works like a façade.

In fact, the resorts take the wall-iconography a step further to apply it to the architecture of their buildings. As seen in the first post on Marrakech on Eikongraphia, the traditional Moroccan architecture is organized around a representational courtyard. The architecture of the resorts however is detached and therefore, in contrast to the traditional architecture, has a lot of façade. What to do? The answer of the developers is to use the wall-iconography for their buildings. The ‘façade’ of the medina has become the façade of the buildings in the resorts.